Confronting the Indigenous player crisis facing the AFL

The AFL is in rude health. Why aren’t Indigenous player numbers?

In light of the AFL’s announcement of the changes to the Next Generation Academy system, I thought I’d put virtual pen to virtual paper to confront a vital question: how can we increase the number of Indigenous players in the game?

NB: Throughout this piece, I’ll be using Indigenous or Indigenous Australian/s (with a capital I) in place of other common terms such as Aboriginal (and Torres Strait Islander) or First Nations. I do so with no intention to cause offence – if I’ve failed at this task, then sincere apologies. I’ll also only be talking about the AFLM.

PS: Apologies about the long time between posts! I had a fairly severe case of day-job overload/writer’s block, but I’m cautiously optimistic this will signal a return to regular posting. Look out for tactical previews of the Qualifying and Elimination Finals soon.

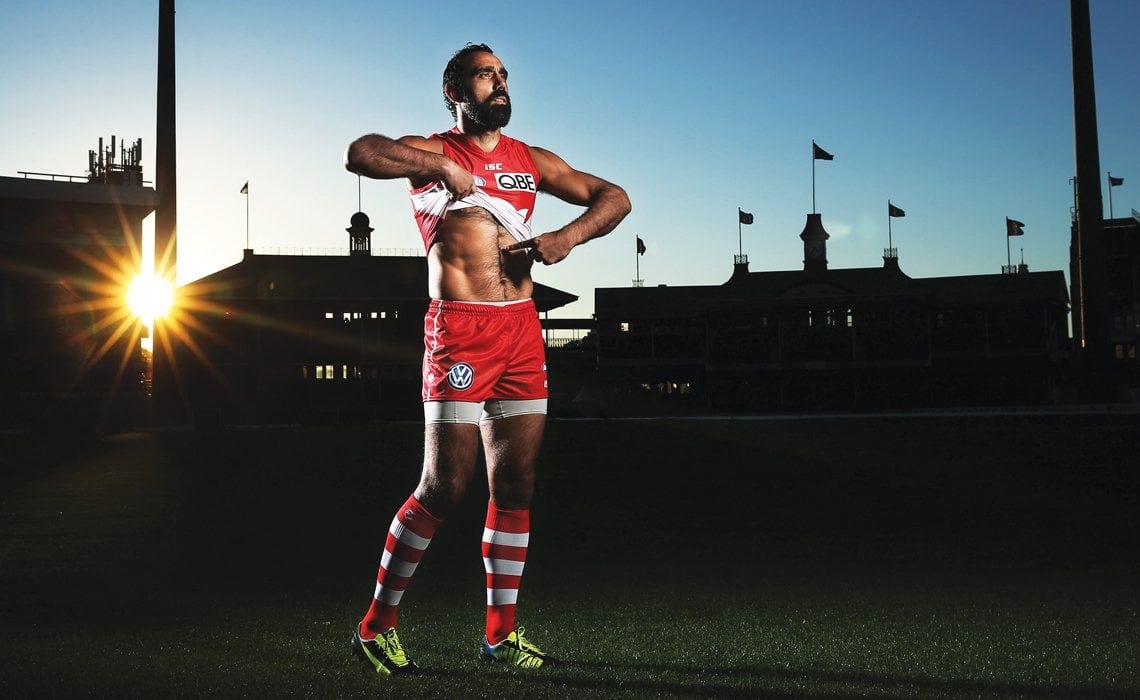

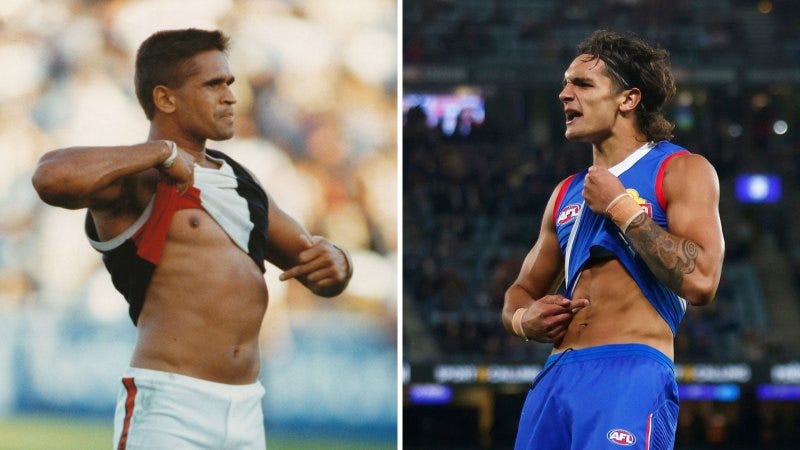

Franklin. McLeod. Goodes. Farmer. Rioli. Krakouer. Winmar. Betts. Pickett. Rankine. Wanganeen. Just some of the names which belong to the Indigenous players who have graced the VFL/AFL. Simply mentioning them is enough to call to mind their most iconic moments and make the hairs on the back of the necks of many footy fans stand up.

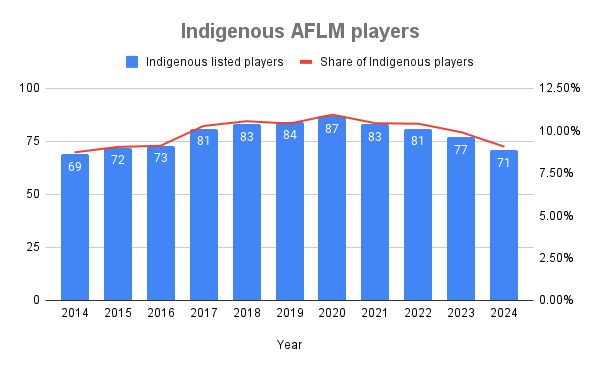

Footy provides a stage for Indigenous men and women to shine, in a country which doesn’t provide them with enough. But there’s a problem. The number of male Indigenous players at the top level of the game is falling. In fact, it’s declined by more than 18 percent since 2020. The AFL is sufficiently concerned about this downward trajectory that, as part of a broader suite of changes to the draft and player trading system, it announced it will relax restrictions on clubs matching bids on players developed through their Next Generation Academies (NGAs). My initial reaction was that it seemed like a band-aid solution to a complex problem. I decided I wanted to know more. Why are there fewer male Indigenous players in the AFL? How likely are the AFL’s proposed interventions to succeed? And what more could the league be doing to ensure that Indigenous players continue gracing our game in abundance?

Before I dive into all of that, it’s worth outlining the assumptions I’ll be working with throughout this piece. I believe they’re all fairly straightforward, and hopefully you agree.

The contributions Indigenous players have made to Australian rules form a cherished part of our nation’s cultural legacy.

Ensuring that Indigenous players, male and female alike, have a fair chance of making it into the AFL/AFLW system is a worthwhile goal.

The AFL is sincere in its desire to curb the decline in Indigenous representation.

With all that out of the way, let’s get stuck in.

How big is the problem of declining Indigenous representation in the AFL? Well, let’s consider the following graph.

There are two distinct eras. Every single year from 2014 to 2020, the number of listed male Indigenous players increased. Since 2021, it’s been in decline. That’s the part of the picture which has raised the alarm at AFL House. There are two points of additional context that’s worth mentioning here. The first is retirements: 19 Indigenous players pulled up stumps between 2020 and 2023. That’s an unusually high number – for comparison, just five Indigenous players (according to my highly sophisticated manual counting method) retired in the preceding four year stretch. Many of those players were champions of the game, like Lance Franklin and Shaun Burgoyne. Others, like Josiah Kyle, a product of the St Kilda NGA who retired without ever playing a senior game, weren’t able to leave as large a mark on the game. We’ve not yet seen the end of the stream of retirements, either. Within the next three years, the likes of Steven May, Brad Hill, Michael Walters and Chad Wingard will all depart the AFL stage.

The other relevant context is list sizes. Prior to 2020, AFL clubs were allowed a maximum of 47 players on their lists, which included between 38 and 40 players on their primary lists, supplemented by up to nine rookies. The reduction in salary caps forced by the Covid-19 pandemic (words which I hope to never write again in this newsletter) resulted in maximum list sizes being cut to 44, with 36-38 of those being senior-listed players. And, some minor tweaks notwithstanding, that’s where they’ve stayed.

So part of the reason there are fewer Indigenous players on AFL lists is that an unusually high number have recently called it quits, and because there are just fewer AFL players overall. Call these the “innocent reasons” – factors which aren’t necessarily indicative of broader problems.

But the much more troubling explanation for why there are fewer Indigenous players in the AFL today has to do with the two primary engines of list turnover: drafting and delisting. Let’s begin with the latter. Of the 84 players delisted following the 2023 season, 14 of them (16.7 percent) were Indigenous. That’s well above that year’s total share of AFL-listed players who identified as Indigenous (9.9 percent). Not a great look. More Indigenous players get delisted partly because they’re more likely to occupy the most precarious spots on a list: Category A and B rookies. That isn’t bad, per se – it could suggest AFL clubs are more willing to take a punt on a raw Indigenous prospect – but it results in the current situation where Indigenous players are delisted at greater rates than their presence on lists implies. There are corollary issues at play, too. Although this would have required a level of number-crunching that I unfortunately wasn’t prepared to do, I’d be willing to bet that Indigenous players, on average, have shorter playing careers than their non-Indigenous counterparts. When you consider that, according to the AFL Players’ Association, the average AFL career already lasts less than six years, you’re not talking about much time in the game at all.

Then there’s drafting. There’s been an alarming drop-off in the number of young Indigenous players in the system. In 2006 and 2008, a combined 44 Indigenous players were drafted to the AFL. A decade ago, 17 were taken in a single year. In 2023, just four Indigenous players were drafted from under-18 level. They combined for a total of 25 games throughout this year’s home and away season. All the evidence suggests the problem will get worse, potentially far worse, before it gets better. Only four Indigenous players were selected for last year’s under-16 national championships, out of well over 100 players overall. Don’t expect Andrew Dillon to call out the names of many Indigenous players in the next few drafts.

Footy fans whose main interest is the AFL tend to see drafting as the beginning of a career. Often, the first time they’ll ever have heard the name of their future hero is on draft night itself. But drafting is also the culmination of a years-long process of talent identification and development, one that requires significant amounts of luck, trust and money to succeed. That goes double for Indigenous players. According to Professor John Evans, Swinburne’s Pro Vice-Chancellor for Indigenous Engagement, the Indigenous talent development model often involves identifying future elite prospects when they’re around 15-16 and then pulling them into the system, which, for those who’ve grown up in rural and remote areas, means a move to the big city and a prestigious private school. That’s quite different to how it works for most non-Indigenous players, who even if they grow up in the country, are often surrounded by a network of clubs, recruiters and other players.

Part of the problem, as described by the recently departed Sam Landsberger in a piece summarising the conundrum and the AFL’s response, is that Indigenous talent development pathways have been deprived of the funding they need to flourish. Less money means that the money that’s still there is deployed more conservatively. So instead of more clubs taking more chances on talented Indigenous kids, they’re being conservative and limiting themselves to the ones who project as obviously elite talents several years before they’re eligible to be drafted. The end result is a bifurcation: the crème de la crème get scooped up, while slightly more speculative prospects are left behind.

Where’s the money gone? Covid (oops, failed already) is undoubtedly part of the answer. But, as one club official apparently alluded to during an all-day session convened by the AFL in March, it’s not that the money isn’t there – it’s that it’s been diverted for other uses. “Save the $1 million you spend on that (AFL Academy) and put it into Indigenous programs and you’ll get more Indigenous (players) drafted,” one club official is supposed to have said in response to a presentation by AFL Academy head coach, Tarkyn Lockyer. If it’s true that the AFL has diverted money away from Indigenous talent development towards elite mainstream development, that’s shocking.

But, when looked at another way, it’s not all that surprising. And this brings me, neatly enough, to the broader topic at hand: the changing nature of how young talent is nurtured. Almost every change made to the way that clubs and the larger AFL system have approached talent development can be boiled down to one thing: reducing risk.

Once you start looking for this, you can see its influence everywhere. Funnelling more money to elite underage programs, such as the AFL Academy, at the apparent expense of Indigenous development. Increasingly stringent testing requirements on prospective draftees. The increasing predominance of a small group of prestigious private schools, who burnish their own credentials by offering promising players lucrative scholarships. Clubs, terrified of whiffing on high draft picks, have instead participated in a joint effort to turn drafting and talent identification into a hard science.

But, for several reasons, that effort has worked to the disadvantage of many Indigenous players. According to Evans, his experience in elite sports has revealed a clear pattern: recruiting Indigenous players “is often perceived as more challenging than selecting their non-Indigenous peers.” That reluctance is partly attributable to lingering stereotypes. For example, kids who were raised in tough circumstances are labelled “difficult” when logistical hurdles mean they miss the occasional training session. Nonchalant body language is perceived as not caring. Shyness? Arrogance. The bias, Evans writes, also extends to the metrics clubs use to evaluate prospective players today. Those tests, he argues, prioritise physical traits instead of football skills, and thus often fail to capture the true potential of young Indigenous footballers. If you’ve spent your adolescence kicking the footy on red earth, then it’s easy to see how beep tests might seem a little alien.

Determination to remove the risk from the drafting process means that players who aren’t on the elite pathway before their 16th birthday are often regarded as permanently lost to the system. And even though some claw their way back through lower league football later in their careers, the vast majority won’t.

Until Australia begins to make significant progress in Closing the Gap, it’s likely that this state of affairs – the conflict between the perception that Indigenous players are a little more risky, and an increasingly rationalised drafting and development system – will persist. And that will ensure that the crisis in Indigenous player numbers continues.

Hence, the AFL’s proposed solution. On August 2nd, the league wrote to all 18 clubs, outlining the raft of upcoming changes to the draft, trade and free agency system resulting from its exhaustive review into competitive balance. Front and centre is the decision to once again allow clubs full access to their NGA prospects, to align with northern Academy and father-son bidding rules. This has explicitly been framed as an effort to arrest the decline in Indigenous representation in the AFL.

Will it work? Folks, I’m sceptical. But before I dive into the reasons why, it’s worth examining the history of the NGA system. Introduced in 2017, NGAs are a joint initiative of the AFL and clubs aimed at “the attraction, retention and development of all talented players (both male and female), whilst growing participation in the under-represented segments of the community.” Under the system, each of the 18 AFL clubs have different NGA zones. Although the desire to reach under-served demographics has always been genuine, NGAs were also an attempt to appease Victorian, Western Australian and South Australian clubs, who grumbled (and continue to grumble) about the existence and productivity of the Northern clubs’ academies.

The NGA system isn’t perfect. Perhaps the most notorious example of its rubbery eligibility criteria is the Adelaide Crows’ James Borlase. James, whose father Darryl won four premierships with the Port Adelaide Magpies across a 246-game career, wasn’t father-son eligible for Port Adelaide’s AFL team (because of Vicbias, of course). However, he was eligible for the Crows’ NGA because he was born in Egypt while his father was working there for the Australian Wool Board. But despite funny edge cases such as these, NGAs have been broadly successful. Jamarra Ugle-Hagan, Mac Andrew and Mitchito Owens are all NGA products.

But this same success has brought controversy. And Ugle-Hagan is perhaps the most emblematic example. Up to and including 2020, clubs could match bids on their NGA products regardless of what point in the draft that bid was made. So despite the Crows bidding on Ugle-Hagan, the Western Bulldogs were able to match that bid using picks 29, 33, 41, 42, 52, and 54. In response to widespread consternation, the AFL capped NGA bid-matching at pick 20 for the 2021 draft before increasing the cap all the way to pick 40 for the 2022 and 2023 drafts. This meant that clubs like Melbourne (with Mac Andrew) and, ironically, the Bulldogs (Luamon Lual) weren’t able to match bids made by other clubs on their NGA products. The recently announced changes revert back to a pre-Jamarra world, where clubs can match bids irrespective of when they were made. The purported rationale is simple: it will incentivise clubs to invest in their NGAs, and, therefore, their young Indigenous and multicultural talent.

It sounds good. In theory. But, as I’ve attempted to demonstrate throughout this piece, declining Indigenous representation in the AFL can’t just be boiled down to a decline in the number of elite Indigenous players. Players like Ugle-Hagan, Shai Bolton, Kysaiah Pickett, and Izak Rankine have all found their way onto AFL lists. But that’s a fait accompli. They were almost certainly always going to end up in the AFL system, both because their talent demanded it, and because they were integrated into mainstream development pathways. The stars find a way. It’s the players who aren’t stars, or whose star qualities take longer to coax to the surface, who are being let down.

I can easily believe that there are natural variations in the level of Indigenous talent. After all, not every National Draft is a “superdraft”. What I find harder to believe – to the point where I’m tempted to reject it outright – is the idea that the abundant well of extraordinary Indigenous footballing talent has suddenly dried up. So how do we reconcile these parallel realities of risk-averse AFL clubs that take an increasingly rational approach to player acquisition, and Indigenous talents that can’t get a fair look because they grew up in a remote area and didn’t board at a prestigious private school?

Any effective response to the precipitous decline in Indigenous player numbers must begin with resourcing. The AFL isn’t exactly short of a dollar. It recorded an operating surplus of $27.7 million in 2023, up from $20.7 million in 2022. Memberships and attendances are at all-time highs. The game is in rude health. So why isn’t Indigenous representation?

I believe there’s a very strong case to be made for the AFL to centralise Indigenous underage development, effectively taking it out of the hands of clubs. What would this look like? It would require the AFL creating a semi-permanent development infrastructure in rural and remote communities to encourage Indigenous talent to flourish. In plain English: more clinics, more competitions, more investment in the regional clubs who give Indigenous kids their first taste of competitive footy, more ways for interested kids to keep playing footy as they get older and nearer to a potential AFL career, and more professional development for youth coaches and recruiters to build relationships of trust with players and their families. This is the biggest lever that the AFL could pull – but there are others. The AFL could create a new class of rookie list spot reserved for Indigenous players, with mandatory minimum contract lengths to incentivise clubs to invest in their development across multiple years. And, of course, the AFL can – and should, without doubt – do more to promote diversity in coaching and corporate leadership roles. There are currently (this information may be slightly out of date, apologies if so) just four Indigenous coaches of any description in the AFLM, and only six clubs with an Indigenous board member.

The AFL is better-placed to assume responsibility for Indigenous development for two reasons: it has more power to affect change, and it has a broader set of interests. Clubs are self-interested. They’ll develop, draft and play Indigenous players if they believe that doing so increases their chances of on-field success. The AFL, meanwhile, is neutral about where Indigenous players play – they simply want more Indigenous players involved in the league. The AFL is also significantly better-placed than clubs to provide pastoral care. If the AFL is serious about its commitment to Indigenous players, then it must also acknowledge its responsibility, as one of the largest institutions that most Indigenous players will interact with, to provide them with the support they need to flourish both during their career and after their time in the AFL system comes to an end.

Although the AFL should take the lead in reversing the decline in Indigenous representation, clubs also have a very important role to play. Principally, they have the responsibility to ensure that they are safe and supportive environments for Indigenous players. We all remember when Adam Goodes was forced from the game because of racist abuse he suffered from opposition fans. Eddie Betts has frequently discussed the additional work AFL clubs need to do in order to become culturally safe environments for their Indigenous players. We’re all more likely to perform to our full potential at work when we feel fully supported by our employers. Footy’s no different.

Trying to decode the mystery of why there are fewer Indigenous players in the AFL today, and how could we begin reversing this trend, has called to mind the quote from the famous American palaeontologist and evolutionary biologist, Stephen Jay Gould: “I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein's brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.”

The talent is there. The passion is there. What’s currently missing for prospective Indigenous AFL players is the opportunity. It seems a forlorn hope to believe that clubs will suddenly be convinced to adopt a less “scientific” approach to talent development and drafting. The costs of falling behind are just too high. They have a role to play. But fundamentally, it’s up to the AFL to cast the net wider and connect more closely with the communities that have produced so much Indigenous talent. And it can’t be an afterthought. It’s core business. The changes to NGA bidding are a step in the right direction. But much larger ones are required.

Sources & further reading:

Explained: How NGAs work, what the AFL's rule change means (AFL – August 2024)

AFL is alert, not alarmed, at fall in Indigenous representation (AFL – May 2024)

AFL Changes Draft, Player List, and Academy Rules (AFANA – August 2024)

The long and complicated history of Aboriginal involvement in football (The Conversation – May 2019)

How private schools have taken over the AFL (The Age – November 2019)

When it comes Indigenous representation, the AFL doesn’t stack up (AFR – May 2023)

Matt Rendell wishes you all the best on this one.

https://www.foxsports.com.au/afl/adelaide-crows-recruiter-matt-rendell-resigns-after-comments-he-made-about-recruiting-indigenous-players/news-story/6416cb92c480602fc11c7096443dea4e