2024 Grand Final preview

One game to rule them all.

This year’s Grand Final is a reminder of footy’s rich narrative possibilities. The two sides, Brisbane and Sydney, are alike in so many ways: perennial powerhouses from rugby league states that prefer to win games and allegiances with glory, not attrition. Both carry the memory of recent heartbreak into Saturday’s decider. Sydney barely caught a glimpse of the Premiership cup in 2022 – it was halfway down the Princes Freeway by quarter-time. The Lions’ pain is more acute. With 10 minutes to go in last year’s Grand Final, they were ahead, only for Collingwood to wrench the cup from their grasp.

Yet for all the similarities they share, in identity and baggage, their paths to the Grand Final could barely have been more different, Sydney assumed top spot on the ladder in Round 8. And, despite a brief wobble, have remained there for the whole season, peering down at their rivals. The Lions ended Round 8 down in the depths of 13th. They have clawed their way here by winning 14 of their last 18 games, including two impossibly dramatic finals wins on the road.

Emotionally and narratively, then, the game is perfectly poised. Both sides have that rarest of things: a chance for redemption. However, there can only be one. Grand Finals are won on the field, in the coaches’ box, and by chance’s mysterious workings. The last of those is beyond my purview. But I can try to write about the tactics.

Last time they met

Brisbane 11.13 (79) def. Sydney 11.11 (77)

If the Grand Final is as good as their Round 19 meeting, we’re set for an all-timer. Sydney, as has been their habit this season, stumbled out of the gates to trail by 22 points at quarter-time. But, uncharacteristically for Swans, they roared back into contention on the back of forward efficiency and potent scoring from stoppage wins. The two sides traded punches in the fourth quarter. The Lions won because they landed a couple more.

The dramatic finish slightly masked the fact that, on another day, the Lions could have won by four goals. Their clearance superiority (+10) allowed them good field position (they went +8 for inside 50s) and a platform from which to dictate the terms of the game. Both sides scored at virtually identical rates from the back and front halves. What ultimately determined the result was injuries to Dane Rampe and Tom Papley and the Lions’ superiority at scoring from turnovers (+28). I’ve written it enough times that I won’t belabour the point, but it’s worth stating once more because it’ll be important later on: scoring from turnovers is the single-biggest source of scores in the modern game. If you can only be good at one thing, make it that. The Lions scored at their season average from turnovers while keeping the Swans to more than five goals below theirs (which has been the best in the AFL). If the Lions can repeat the feat on Saturday, they’re halfway to heaven.

Why Sydney will win

There are three important factors working in the Swans’ favour. The first and simplest is fatigue. They’ve only played two games in the last month and haven’t left Sydney for even longer. They were able to play at half-intensity for the final quarter of their Preliminary Final. Compare that to the Lions, who’ve just played to the final whistle in two exhilarating, exhausting finals away from the home comforts of the Gabba.

The second is personnel. Being without their captain, Callum Mills, will be a blow. But I think it’s one that will be felt more psychologically than tactically. The Lions, meanwhile, will be without their number one ruck, Oscar McInerney. Given his importance to their stoppage set-up, that feels like a far bigger loss, especially (as you’ll read in the Brisbane section) the importance of field position to the Lions’ game plan.

The third is flexibility. In my lead, I mentioned that Sydney had suffered a late-season wobble. That rather undersold it. It was a full-blown slump. OK, three losses by a cumulative total of five points can easily be attributed to bad luck. But losing by 39 and then 112 points in consecutive games against other finals contenders… well, that’s the height of carelessness.

But, harnessed correctly, adversity breeds strength. John Longmire and his assistants recognised that other sides were cottoning on to their methods, and adjusted accordingly. It all boils down to how the Swans use the ball. Amid all the (richly deserved) hype for their fleet of agile attacking midfielders, it can sometimes be forgotten that Sydney are principally a kick-mark team – just a very precise, aggressive one. They’re ranked 4th in the AFL for kicks as a share of disposals and 5th for marks. All year, the Swans have used short, precise in-board kicks to open space in high-value parts of the ground, and from there exploited the speed and agility of players like Chad Warner, Nick Blakey and Errol Gulden to either carry or deliver inside 50.

But in the elite competitive environment of the AFL, if your game plan has a vulnerability, teams will find it. The Lions weren’t the first team this season to have more points than the Swans when the final siren went. But they were perhaps the first to really beat them tactically. By packing the corridor and denying them short options from half-back, they forced Sydney to kick long down the line 22 times in that Round 19 game, twice their previous season average. Other teams followed suit. Since then, the Swans have kicked long down the line an average of 17 times per game – more than all but one side. They’ve become slightly less potent as a result. But, in creating more margin for error when they have the ball, they’ve arguably found a more sustainable balance between attack and defence.

Since their slump, Sydney have become slightly less potent, but more pragmatic. Whereas previously they’d thrust forward even if the opportunity wasn’t quite right, now they’re more willing to wait for the right moment. Over the last five games, the Swans are taking an extra 8.6 marks and 4.2 kicks per game, and conceding almost seven fewer turnovers per game. These are subtle differences. We’re talking about moving sliders, not ripping up and starting again. But these differences have been matched by what the Swans are doing when they don’t have the ball. Consider the following:

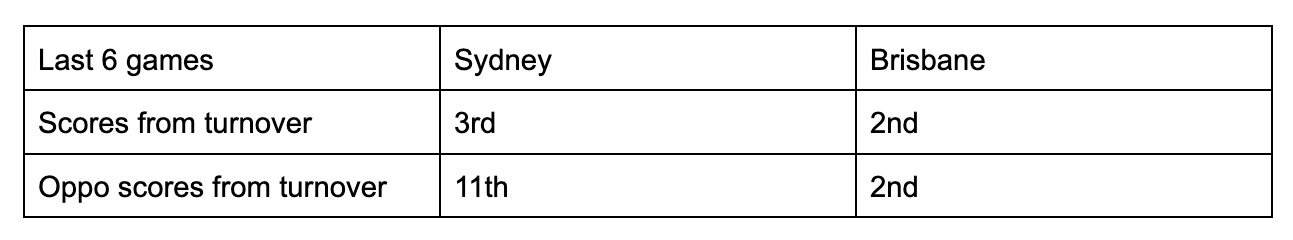

To me, those numbers reflect a realisation that the Swans’ ultra-aggressive approach of the first two-thirds of the season was allowing their opponents too many opportunities to hurt them. Now, Longmire’s side is trying to assert slightly more control while allowing their opponents less of it. They’re conceding fewer turnovers, in less dangerous areas of the ground (like near the boundary), while ensuring they’re still able to win it in high-value spots. It’s working. Over the last five games, the Swans are averaging +18.6 points from turnover, compared to their season average of +11.1. When you consider that all eight finals this year have been won by the side that’s scored more points from that source, it’s a promising sign.

The other cause for optimism is that this evolution – maturation, one might say – in Sydney’s defensive profile is the ideal blueprint for nullifying Brisbane’s preferred style. I’ll explore this in more depth in the next section, but to beat the Lions, you need to deny them the opportunity to advance the ball up the field by foot. The Lions have taken more than 100 uncontested marks in 12 games this season. They’ve won 11 of those games. The Lions love control, which usually begins by winning the ball from stoppages. But here’s where we get to the unique cruelty of Grand Finals: the players who play almost every game except for this one. Oscar McInerney, Brisbane’s main ruckman, won’t be playing. His absence opens the door for Brodie Grundy and the rest of Sydney’s midfield crew to gain the ascendancy from stoppages. If the Swans can do that, their slight edge in other parts of the ground ought to give them the overall advantage.

I’ve probably lingered a bit too long on the changes Longmire has made to Sydney’s defensive set-up. They’re important, especially because of the specific dynamics of the Grand Final. But it’s really worth reinforcing that the main reason the Swans finished first, thus securing themselves the double chance and easier passage to the Grand Final, is because of their awesome scoring power. They are a multi-faceted attacking threat. It begins with the Big Three: Warner, Gulden, and Isaac Heeney. Each provides something subtly different. Heeney, for so long a half-forward with midfield stints, has been moved to the coalface and has blossomed into one of the game’s premier goal-kicking midfielders. His marking prowess makes him a nightmare match-up. Warner’s agility allows him to weave his way through traffic and get involved in damaging chains, which often end with him having a shot on goal or delivering to a forward. And Gulden uses his own evasion to find space, receive the ball, and use his exquisite foot skills to find targets. All these players are equally adept at creating goals for others as they are kicking them themselves. An underrated reason why the Big Three wreak so much havoc is because their defensive support has improved. The astute addition of James Jordon and continued development of James Rowbottom has provided the Swans with a defensive discipline they’ve lacked – they’ve gone from having the 13th-best scores from stoppage differential in 2023 to the best this year. Elsewhere, Blakey and Jake Lloyd provide back-half thrust. Tom Papley is one of the league’s best small forwards, and Will Hayward is one of its better medium forwards. And although the Swans’ key position forward stocks won’t strike fear into many hearts, they provide enough of a threat in the air and at ground level to facilitate their stars. This is a side whose Plan A was already good enough to win most games, and who, in the last month and a half, have developed a robust Plan B.

Why Brisbane will win

To once again employ the Control vs. Chaos framing introduced by Champion Data’s Daniel Hoyne, 80 percent of finals games are Chaos Games (meaning they have more ground ball gets than marks). The basic theory is that greater stakes and janglier nerves induce more pressure and a higher number of errors, which creates more congestion, which creates more… chaos. For most, I’d say almost all, of Chris Fagan’s tenure, Brisbane have preferred control. They win the ball, either directly from stoppage or by forcing an opposition turnover, and then methodically move it by foot until they find a mark inside 50. No mark? No problem. Thanks to the wiles of guys like Charlie Cameron, the Lions have been one of the competition’s best forward-50 stoppage teams for years. If that multidimensional attacking threat reminds you of their Grand Final opponents, you’re not wrong. There are subtle differences, of course. The Swans prefer to either run it out of their back 50 or spread it wide before bringing it in-board, whereas the Lions are the league’s most “vertical” side. Pay attention to how often a Lions player kicks it more or less directly forward from where he receives the ball, and you might struggle to stop seeing it. The Lions are better at stoppages, while the Swans edge the “post-clearance” game. But the fundamental point remains the same: two sides, both brimming with talent, that both prefer to control the terms of the game.

The second half of their thrilling Preliminary Final against Geelong showed that Brisbane have added another string to their bow – and, in the process, have embraced chaos. After losing Oscar McInerney, and seemingly resigning themselves to losing the upper hand from stoppages (and Joe Daniher from their forward line), the Lions totally changed their ball movement scheme. It was about two words. Run. And carry. After taking just 39 uncontested marks in the first half, the Lions took that many in the third term alone. They still kicked at about the same rate as earlier in the game. However, the big change was their intent by hand. The Lions gained more than 500 metres via handball, the first time any side has done that in a final since… Richmond in 2017. Brisbane spread the field beautifully by drawing Sydney players, in turn creating space in their forward 50 for the likes of Kai Lohmann to lead into. It was truly impressive, partly because it was so unlike the Lions we’ve come to know so well.

John Longmire would have been paying very close attention. But one of the great benefits of tactical versatility is that even the knowledge that a team has different styles they can adopt can sow uncertainty in the mind of the opposition.

If the Lions have learnt how to supplement control with the power of chaos, then the Swans haven’t quite managed the same mastery. Take a look at this:

One of these things is, plainly, not like the other. We’re not talking about big absolute numbers here. However, we are talking about one team having a noticeable weakness which aligns with one of their opponents’ principal strengths. Part of the reason Brisbane fares so well on this metric is that, owing to their clearance strength, they tend to play the game in their half. The ball is closer to their attacking goal, and further from their defensive goal, more of the time. That’s the other major discrepancy between these two evenly-matched sides: clearances.

Brisbane are ranked first in the AFL this year for clearances per game (partly a function of their stoppage-heavy style) and second for clearance differential. Narrow the focus to just the last five games, and their rankins is exactly the same on both metrics. The Swans don’t fare nearly so well. They’re 12th for clearances and 7th for clearance differential. There’s a growing consensus that clearances are poorly correlated with winning games. While it’s true that what you can do after the clearance matters more, that doesn’t mean clearances themselves are irrelevant. I think the best way to think about clearances is twofold: firstly, they’re a way to advance the ball up the field. And secondly, they deny your opponents a potentially dangerous scoring opportunity. The Swans are actually a very good side at scoring from stoppages (3rd in the AFL – just behind Geelong and the Western Bulldogs). But part of that is contingent on winning or, at the very least, breaking even in the stoppage count. Last time they played, Brisbane won the clearance count by 10. Sydney can’t let that happen again.

Enjoying my Grand Final preview? Please consider sharing it with a mate!

Five questions that matter

Can Sydney nullify Brisbane’s clearance strength?

Can Brisbane stifle Sydney’s run off half-back?

How often will Sydney seek the corridor?

Who gets the match-up on Isaac Heeney?

Will Brisbane employ the same forward-handball style as against Geelong?

Who will win?

Nice try. But you know I don’t do that here.

Final word

I’m really excited about this game. With apologies to Cats, Port, Dogs and Hawks fans, it feels right – like a meeting of the two most deserving sides. The Swans have been imperious. The Lions have been brave. Both have learnt how to play different styles at high levels. One will complete their arc, while the other will suffer a second helping of heartbreak. However, both sets of fans should derive some measure of comfort from the knowledge that, regardless of the result, their clubs are set up for sustained success.

That’s it from me for a couple of weeks. I have a piece in the works which I’m really excited about – all going well, it’ll be ready during Trade Week. From there, my goal is to publish a handful of longer, feature-style pieces before turning my full attention to my 2025 season previews.

I’m very easily influenced. So if you have an idea for a topic you’d like to see me cover, please tell me about it. Perhaps you’d enjoy reading a tactical deep dive of a past team, or a review of a particular game, or to know my thoughts on the Northern Academies. I always love hearing from readers, so please – don’t be shy. And as always, thanks for the support. I have this crazy dream of turning One Percenters into my full-time job. But for that to happen, you need to subscribe and share. If every subscriber shared this preview with a friend or two, then that crazy dream would already start looking a little nearer.